By Daniel Swain, Stanford University April 1, 2016

One of the big questions in the news this winter has been: When will the drought be over?

A study published today in Science Advances suggests that may not be the most useful question to ask. Better might be: Is the climate of California starting to see even wider swings between dry and wet conditions? We’re already a land of “feast or famine” weather. How will we manage our water future if we’re experiencing greater extremes?

A team of us from Stanford, Northwestern and Columbia conducted the study to find out whether the atmospheric conditions associated with California’s most extreme wet years or most extreme dry years are happening more often.

The short answer? Yes. The atmospheric pressure patterns we see off the coast of California during extreme dry years are happening more frequently in recent decades—and the patterns that lead to our wettest years may be becoming more frequent as well.

What Happened During California’s Extreme Drought?

Since early 2013, the state of California has been in the grip of an extraordinary multi-year drought. The accumulated loss of precipitation over the four years so far is unprecedented in the century we’ve been recording this information. If you add the drying effects of record-high temperatures, the 2013-2016 event may, in fact, be the most severe in a millennium.

The amount of water stored in the critically important Sierra Nevada snowpack reached its lowest level in over 500 years in 2015, and the loss of groundwater in the state’s aquifers has literally moved mountains.

The drought has had widespread effects on the state’s economy and environment, slashing the amount of water available for agricultural and urban uses, raising wildfire risk and dramatically increasing tree mortality. Across the state there have been adverse effects upon riverine and marine ecosystems and infrastructure damage to roads and pipelines.

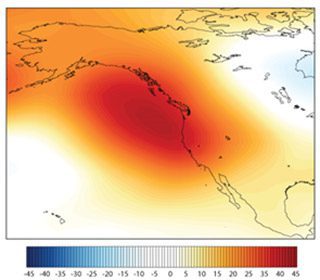

The Ridiculously Resilient Ridge, Oct-May 2012-2015. (Adapted from Swain 2015, GRL)

The atmospheric pattern responsible for ushering in this record-breaking warmth and dryness is the now-infamous “Ridiculously Resilient Ridge.”

The RRR is an unusually persistent stretch of atmospheric high pressure sitting over the Pacific ocean off the coast of California. This sluggish Ridge hovered right in the path of storms headed for the state. Like a boulder displacing a narrow stream of water, the RRR consistently deflected water-bearing storms to the north of California, precisely during the typical “rainy season” months of October to May.

Much of the state was therefore left high and dry—even during what is typically the wettest time of year.

California Is Unusually Susceptible

We get the majority (66%) of our annual precipitation during just the four months of December through March. Unlikely many places on Earth, our summers are very dry: less than 5 percent of our precipitation falls between June and September. And we don’t tend to get our annual water supply from a large number of storms. Remarkably, most of California’s precipitation in a typical year falls over the course of a relatively small number of strong storms.

Related Stories:

Here’s why: the state lies just south of the typical winter storm track in the Pacific, so Californians have to rely on the rain and snow that falls when the jet stream dips south—and it does this for relatively short intervals—sending storm systems barreling toward our coastline.

The most important of these storms are associated with “atmospheric rivers.” These narrow plumes of concentrated atmospheric water vapor bring tremendous amount of rains mountain snowfall when the move inland—increasing flood risk but also bringing much needed water to the Golden State.

This striking dependence of California’s entire water supply upon the occurrence of just a few atmospheric river events each winter means that a surplus or deficit of just one or two such storms can quickly increase the risk of flood or drought in any given year.

As a result, diversion of the Pacific storm track by unusually persistent winter ridges is the most common cause of California droughts, since there is little opportunity to make up for accumulated water deficits during the rest of the year.

Patterns Associated With Drought Are Occurring More Frequently

Our team investigated whether North Pacific pressure patterns similar to those we saw during California’s most extremely dry, and wet periods were occurring more frequently in recent decades. We looked at the years from 1948 through 2015, and the months of October through May.

We found that certain unusual atmospheric patterns are indeed occurring more often. Over the past three decades, we’ve experienced more frequent patterns similar to what we saw during California’s extremely warm and dry years of 2013-2014 and 2014-2015.

These years—during which the Ridiculously Resilient Ridge rose to prominence—were characterized by unusually low pressure over the Pacific north of Hawaii, and a very strong ridge of high pressure along the entire West Coast of North America, from southern California all the way to the Alaskan arctic.

Long-term trends in California drought severity (upper left), temperature (upper right), Sierra Nevada snowpack (lower left), and precipitation (lower right). The red shaded regions depict the 2013-2015 drought. (Adapted from Swain 2015, GRL)

But Not at the Expense of Wet Year Patterns

Given the increase we saw in pressure patterns similar to California’s driest years, it might be reasonable to expect that patterns associated with the wettest years have become less common. But that’s not what we found.

Instead, one of two methods we used in this study suggested that several wet patterns have actually increased in recent decades, while the other suggested little change. Therefore, while we are quite confident that patterns conducive to extreme warmth and dryness in California are happening more frequently, this does not seem to be at the expense of those patterns associated with California’s wettest years.

‘A Strong and Persistent Ridginess’

A number of studies have already shown that the long-term temperature trend associated with global warming has increased the likelihood and severity of drought in California—even when there are no significant changes in precipitation.

Our new work demonstrates that increasingly frequent atmospheric patterns conducive to extreme drought in California are indeed increasing, but that patterns conducive to very wet years may also be increasing.

We haven’t traced the exact cause of this increase in patterns similar to the Ridiculously Resilient Ridge, but we do find there’s an increasingly strong and persistent “ridginess” off the West Coast.

Finally, it is worth noting that climate models for 21st century California depict a much warmer future, likely accompanied by increasingly large swings between dry and wet conditions.

It is fascinating that such large changes in the character of California precipitation are occurring despite little long-term change in average precipitation—which highlights the critical importance of considering changes in the most extreme years when planning for the future.

Daniel Swain is an atmospheric scientist at Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences. A version of this post also appears on his California Weather blog. Other authors on the study published today are: Daniel Horton, Northwestern University; Deepti Singh, Columbia University; and Noah Diffenbaugh, Stanford University.